What are women willing to do for power in a man's world?

This production, set in early 19th century China, explores the true story of Shih Yang and her rise from prostitution to her command of one of China’s most ruthless pirate combines. We know that she married a gang leader named Cheng I, but how were they able to forge a confederation of pirate fleets that numbered 80,000 strong? When her husband died, how was it that the Widow Cheng was elected the Paramount Admiral of the combined pirate fleet? Was it her charisma that enabled her to transform the pirate’s violent activities to the more lucrative and stable business of protection and extortion?

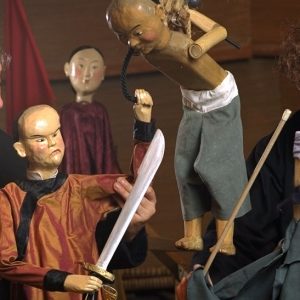

Pirate Widow Cheng is performed with a wide range of puppetry techniques that include table-top, halogen shadow, object theatre, and human size figures.

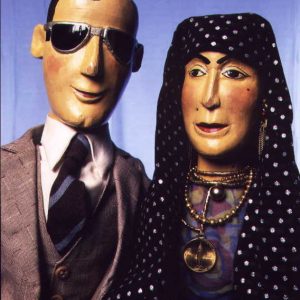

A theatrical convention devised for this production was a visual caste system to distinguish between the core characters, the secondary characters and the faceless masses: Cheng and her immediate family were highly detailed and realistic, the other admirals had object heads on realistic bodies (e.g. a rock, a piece of drift wood, a bundle of rope), and the lesser pirates, officials and population were sticks with simple fabric hinting at costume. The play was staged mainly on two wheeled boxes, that were regrouped and reconfigured to represent the many locations and scenes needed.

ARTISTIC TEAMS

First version: Performed as a co-production at the Center for Puppetry Arts, Atlanta in 2000

Directed by Jon Ludwig, designed and built by Ann Powell and David Powell, performed by Ann Powell and David Powell and Lorna Howley, with music by Klimchak, and light design by Liz Lee.

Second Version: Played at the Tarragon Theatre Extra Space in 2002

Directed by Mark Cassidy, designed and performed by Ann Powell and David Powell, music by Darren Copeland, lighting design by Gareth Crew, set dressed by Wendy White, and stage managed by Varrick Grimes

Awards and Reviews

Nominated for two Dora Mavor Moore Awards in the Independent Theatre category, for Outstanding Set Design and Outstanding Music.

REVIEWS

The Canadian première (of the Pirate Widow Cheng) now playing at the Tarragon Extra Space reveals the Powells as storytellers of boundless imagination.… performed with such gusto… Their imagination makes you feel the sense of play in “play”. Christopher Hoile, Stage-Door

…stunning… They are experts at infusing a puppet’s de facto wooden gestures with palpable emotion…The Puppetmongers’ intriguing images succeed in provoking the mind with their deliberate theatricality… Rebecca Caldwell, Globe and Mail

The Powell’s low-key manner taps into our facility for imagining that we might have thought had died out in us with adulthood. Their imagination makes you feel the sense of play in “play”. The show is performed with such gusto I can’t help smiling when I think of it. Christopher Hoile, Theatreworld

There seems no end to the company’s ingenuity of expression… EYE Magazine, Toronto

“Hurrah for the Pirate Queen” When is a piece of wood not a piece of wood? When it’s in the hands of a puppeteer. That’s what you realize when you see Puppetmongers at work. Anything held by brother and sister Ann and David Powell can become animated, even a plain wooden stick. Puppetmongers are best known in Toronto for their shows for children at Christmastime. “The Pirate Widow Cheng”, their first production for adults, premiered last year at the Center for Puppetry Arts in Atlanta, Georgia, and played to sold-out houses. The Canadian première now playing at the Tarragon Extra Space reveals the Powells as story-tellers of boundless imagination.

“The Pirate Widow Cheng” is based on one of those true stories that is stranger than fiction. The Powells first came across it in Jorge Luis Borges’s “A Universal History of Infamy” and further researched it in the work of historian Dian H. Murray. Shih Yang was sold in infancy and raised to become a prostitute. She married a pirate gang leader Cheng I, but after his death, remarkable as it may seem, she was elected to succeed him as Paramount Admiral over a combined fleet of 80,000 pirates who sailed the South China Sea from 1801-1810. Under her tutelage the pirates transformed themselves into a protection and extortion ring thus guaranteeing themselves a more dependable livelihood. The Chinese Empire had no way to deal with them but to grant them amnesty and absorb their practices.

To tell the story Puppetmongers, aided by design collaborator Wendy White, have transformed the Tarragon Extra Space into what looks like a Chinese doll store. The audience enters through a beaded curtain and walks through the set to a room lined with rattan mats and with cushions for seating in the front row. A life-sized puppet of Shih Yang as an old woman looks down on the action from the top row. Ann and David Powell, clad in black, frogged Chinese suits, introduce themselves and then their large cast of characters. According to a kind of puppet hierarchy, the main characters, about one-fifth human size, have moulded faces and rich-looking costumes, but the secondary characters are smaller and have no faces at all, one clearly a former newel post, another a piece of bamboo, until we meet even smaller characters, “the faceless masses”, who are truly only a raw wooden sticks with a few rags tied round them.

Unlike Ronnie Burkett, who uses exquisitely carved marionettes, one-third human size, all in elaborate costumes, Puppetmongers clearly want to lay bare, literally, what their puppets are. Their suggestion and manipulation activating our imagination animate what is so clearly inanimate. This also applies to their sets. Two cabinets on casters joined end to end become a ship, side to side become two ships circling and then attacking each other. The Powells’ low-key manner taps into our facility for imagining that we might have thought had died out in us with adulthood.

The 90-minute play is for adult audiences because of its language, brutal violence and frankness about prostitution and homosexuality (Cheng I is more devoted to his male lover than to Shih Yang.) The Powells also present the action from a dual perspective that would not interest children. Just as they were the intermediaries for the Powells, Borges and Murray (David and Ann as actors) are our narrators, half human, half puppet, whose views of the action are contradictory, Borges romanticizing it, Murray insisting on known fact and detail.

While Ronnie Burkett’s works are really full-fledged plays enacted by marionettes, Puppetmongers practice primarily tabletop bunraku, the larger puppets manipulated on an elevated surface by two puppeteers rather than the three of classical Japanese bunraku. Their work is more related to physical theatre with its emphasis on action over words. The most memorable scenes are the numerous battles like the hilarious parody of the fighting scene atop the bamboo in “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon”, the pirates of Cheng I attacking and boarding a rival vessel and the beautiful use of shadow puppets to show the pirates sacking and burning a village. Puppetmongers play with abrupt changes of perspective as when Shih Yang changes into her tiny acrobatic self and back again. The most amazing example of this comes near the end when on top of a cabinet, the Powells using what are simply stones and blocks of wood, recreate peaceful life in a village before a sudden pirate attack represented by a downpour of chips of wood.

The story is so rich in implications it’s no wonder the Powells have been exploring it for more than three years. The cost of survival, the objectification of women, the close relation of capitalism and exploitation, the uses of history are all themes the story raises. While the actions the Powells create are exciting, I would have welcomed more interpretation of the story’s many ironies. Shih Yang’s reactions to events are shown primarily in silence. The Powells want us to put ourselves in Shih Yang’s place, but I would have been glad to learn her perspective more directly from her.

Director Mark Cassidy has given the piece admirable clarity and pacing Yvonne Ng has provided the choreography most notable in the expressive dances the young Shih Yang performs to attract Cheng I. Gareth Crews’s evocative lighting along with Darren Copeland’s highly effective soundscape help underscore the play’s many shifts of time, place and mood.

Anyone willing to try something different should experience “The Pirate Widow Cheng”. The show is performed with such gusto I can’t help smiling when I think of it. I remember rooms long ago where anything inside could walk or talk if I wanted it to. The Powells bring you into one of those rooms again. Their imagination makes you feel the sense of play in “play”.

Christopher Hoile, Principal Reviewer for Stage Door